Russian cargo jet grounded in UP 16 years may soon fly again

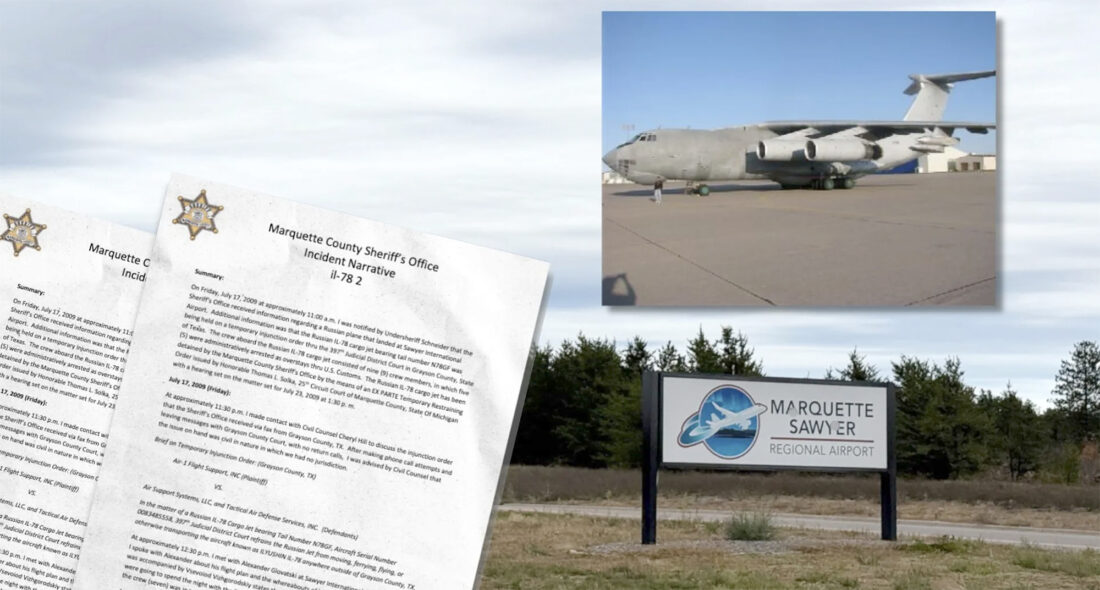

The Russian cargo jet shown in this photo illustration has been grounded at the Marquette airport for 16 years after police enforced a restraining order prohibiting it from taking off. After years of legal wrangling and changing ownership, the plane could soon fly again. (Image of plane courtesy of the Marquette County Sheriff’s Office)

(This story was originally published by Bridge Michigan, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. Visit the newsroom online: bridgemi.com.)

One of the Upper Peninsula’s most enduring sagas — the grounding of a Russian cargo jet marooned near Marquette for 16 years — may soon come to an end after years of lawsuits, police investigations and feuding over ownership.

The tale that touches Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Pakistan and Texas and involves expired visas, an unpaid mechanic, multiple financiers, the local sheriff and the FBI may soon end with the plane flying again.

All thanks to wars in Gaza and Ukraine that a representative of the plane’s owner says have dramatically boosted the aircraft’s value to $50 million from $12 million.

“There’s been an uptick in activity, simply because of the ongoing things in the Gaza Strip and likewise with the war in Ukraine and Russia, so there’s companies out there that are investing and purchasing all kinds of air cargo airplanes,” Dwight Barnell, a broker who has maintained the plane through its multiple owners over the years, told Bridge Michigan.

The plane, a Russian Ilyushin IL-78 cargo plane built in Uzbekistan and sold out of Ukraine, landed at Marquette Sawyer Regional Airport in Gwinn on July 17, 2009, to refuel.

It never took off. Half of its crew was detained by immigration officials that night, including the pilot, and the local court ordered the plane grounded while at least six creditors both foreign and domestic fought over who should control the aircraft.

The whole case is “quite unusual,” said Cliff Maine, who has worked in aviation law for decades and is familiar with the plane. “And you need unusual characters.”

Barnell said the plane’s owners have for years spent about $1,000 a month storing the plane in Gwinn amid an ownership struggle.

Now, the plane has a clean title and its current owner, Philadelphia consulting firm Meridican Inc., is readying it for sale. He said two to three entities have expressed interest in the aircraft.

The Ukrainian engineers needed to inspect the plane have been caught in the backlog of visa applicants since the weeks-long government shutdown that ended in mid-November.

Once those engineers inspect the plane, a sale can be finalized, and then it’ll take three to four months to get it ready for flight, Barnell said.

“It’s been a long time coming,” Barnell said. “We’re excited to get it off to its next chapter of life.”

If the plane flies again, it’ll cap a yearslong battle that snaked its way through state and federal courts and captured the attention of national news outlets and Marquette residents who called the plane “Boris the Tanker.”

“It’s something that’s well-known about … so I’m sure it’s something that people will know that it’s gone,” David Erhart, manager of the Marquette airport, told Bridge Michigan.

“To see it have new life is what we’d hope for for the aircraft owner.”

‘Cop cars coming out of everywhere’

The messy affair came to the Upper Peninsula when the phone rang at the Marquette County Sheriff’s Office at 11 a.m. July 17, 2009.

An attorney representing a Texas mechanic told a Marquette County deputy that a Russian plane had landed despite a Grayson County, Texas, judge’s order that the plane stay in Texas. The Texas mechanic had sued the plane’s owners over unpaid bills, according to police records Bridge Michigan obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

As well, the caller said, some of the plane’s crew were Ukrainians in the country on expired visas.

Barnell said that, when he and his crew disembarked in Gwinn, “all of a sudden, the whole airport lit up, cop cars coming out of everywhere.”

When police interviewed the pilot, he told them the crew had stopped in Marquette to refuel and was enroute to Iceland and eventually Pakistan.

Barnell told Bridge he had a lease on the plane at the time and was rightfully headed to Pakistan, where it would be used in military training. He said nobody told him the mechanic hadn’t been paid. They’d landed in Gwinn to buy $100,000 worth of fuel and to hand paperwork to US Customs that would allow the plane to leave the country.

Later that day, a lawyer for the plane’s owner, a Delaware outfit called Air Support Systems, called police to say the plane had been stolen and its owners “had no idea who was even flying the cargo jet,” according to the police reports.

Police initially determined they had no jurisdiction because the Texas court case was a civil matter. When calls kept coming in from Texas, however, the Sheriff’s Office decided to call the FBI.

The FBI interviewed the crew and then called US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, who detained five of the nine-member crew — including the pilot — for expired paperwork and took them to Sault Ste. Marie for processing. The plane couldn’t go anywhere.

Barnell said the crewmembers had overstayed their visas by a few days and they turned in the proper paperwork in Gwinn.

“We did everything absolutely, positively correctly,” he told Bridge.

Meanwhile, the Texas mechanic hired a Marquette lawyer who obtained a restraining order from a Marquette County judge saying the plane had to stay put.

Police called the airport manager, who provided two sander trucks and a runway snowplow to box the plane in.

Police pinned a notice of the restraining order to the door of the plane.

The fight was just beginning.

Heavy debt and a battle for control

By the time the plane landed in the U.P., the drama was already four years old.

North American Tactical Aviation, a Delaware company headed by Barnell, bought the plane for about $4 million from Tashkent Aircraft Production Corp., a Ukrainian company, in July 2005, according to Federal Aviation Administration records.

The plane — with a 165-foot wingspan, 152 feet long and 48 feet tall, weighing capable of hauling nearly 375,000 pounds — is designed for mid-air refueling but, when the big fuel tanks are removed, it becomes a large, versatile cargo plane capable of hauling large vehicles.

Barnell told Bridge Michigan he couldn’t find work for the plane. He explored using the plane for firefighting, but “the last thing that would ever happen is allowing a Russian tanker to come in and take away business from existing companies that utilize 100% American airplanes,” so he abandoned that idea and decided to sell the plane.

Air Support Systems bought the plane in 2005.

Debt started piling up.

In September 2008, Air Support Systems took out a $1 million loan from Headlands Limited, a Gibraltar company that has business in everything from tech to restaurants, and put the plane up as collateral, according to the FAA records.

But Headlands was just one of several companies who said Air Support Systems owed them money. By the time the case landed in Marquette County courts in 2009, a half-dozen outfits were clamoring for control of the plane.

It would take eight years to sort it all out and for a judge to give Headlands the right to sell the aircraft. Meridican bought it in 2019.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, air cargo business dried up again, and Meridican sat on the plane for several more years.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine.

Then Hamas attacked Israel, and Israel reciprocated.

“The value has skyrocketed in the last, I would say, 2 ½ years,” Barnell said.

Ready to fly again

In the interim, Meridican hired Barnell to look after the plane.

It’s regularly inspected, powered up to make sure the systems work, the engines “cold turned” with a wrench to make sure they aren’t seized up. Still, it’ll take about $500,000 to run through all the factory inspections to make sure the thing can fly again.

“It’s in long-term preservation storage, and, even though it looks like crap on the outside, there is no major corrosion of any kind, whatsoever,” Barnell said. “We’re flying a very safe airplane, doing everything in accordance with the manufacturer.”

When he bought the plane 20 years ago, it had been sitting for 10 years, Barnell said. He went through the same exercise then to get it from Ukraine, and he had no doubts the plane would someday soon take to the skies.

“I would not use the word ‘might,'” Barnell said. “It will take off.”