Who’s behind the creation Ludington Park?

R. R. Branstrom | Daily Press Dr. Charles Lindquist, local historian, discusses important persons from Escanaba’s past who were influential in the city’s early days. The talk, organized by the Delta County Historical Society, was hosted at Bay College’s Heirman Center.

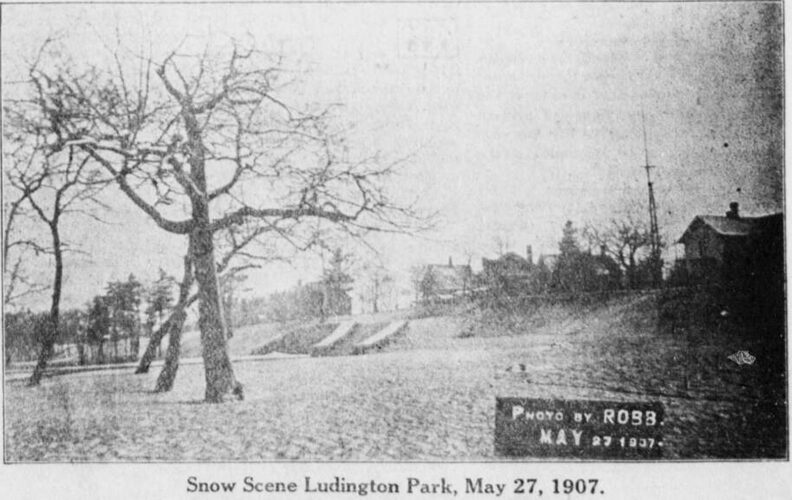

Courtesy photo

This 1907 photograph, published in the Escanaba Morning Press is 1909, is one of the earliest captured of Ludington Park. The park was created largely thanks to the efforts of Solomon Greenhoot, who was mayor around the turn of the century, Belle Greenhoot, and Escanaba citizens who voted for a bond to purchase the land for the city.

Solomon had immigrated to the area in 1870 from Bohemia and for years ran a dry goods store alongside his brothers, Simon and Julius. During and after transitioning out of the retail business, Solomon and Julius bought and sold hundreds of thousands of acres of timberland throughout the U.P.

In the early 1890s, Solomon Greenhoot ran for mayor of Escanaba with one of his platforms being that he wanted to establish a park named after Nelson Ludington, the man who had in the mid-1800s purchased large tracts of land in the Upper Peninsula and built mills at Escanaba and Marinette to supply the N. Ludington and Co. lumber business, which was headquartered first in Milwaukee and then Chicago.

After electing Solomon as mayor in 1892, voters approved that very November a bond proposal to buy land on the south side of Sand Point for a park. It took a long time to come together, but by 1896 the land was acquired. Seeing that development had yet to begin in 1899, Solomon’s wife, Belle Greenhoot, invited the city’s park committee to the Greenhoot home — built at the corner of Lake Shore Drive and Fourth Street in 1886 — to restimulate plans.

Mrs. Greenhoot was formerly Belle Rindskopf of Milwaukee.

“Not long after (the meeting hosted by Belle), the city engineer began to lay out the grounds of the park, and grading began to be done as well,” wrote Lindquist in a book about early Escanaba history.

Photos from the early 1900s show citizens enjoying the public park prettily scattered with trees, benches, and pathways. Though some scenes in artwork of the early 20th century refer to it as “New City Park” and “Bay Shore Park,” Escanaba’s mile-long recreational land south of Sand Point has long been officially called Ludington Park — just as Solomon Greenhoot intended. The city ordinance designating and naming Ludington Park was adopted in 1914 under the mayorship of Oliver Chatfield.

While Solomon’s first stint as Escanaba mayor may have begun with a park platform, his later term in that role featured around cleaning up the city, spurred by a plague of typhoid fever that had struck area residents. He focused on the city’s completion of a filtration plant connected to the water plant, cleaning the alleys, putting in new sewers and filling outhouse vaults and cesspools.

“‘Cleanliness is next to godliness’ is a wise saying, and I wish that it might be the motto of every person in the city. Let us have conditions here that will awaken and develop a great and truer civic pride,” Solomon said in an address to Escanaba City Council in April 1909.

Belle Greenhoot, in addition to helping with efforts to create the park, also provided another service to Escanaba. She offered her home as an emergency station if ever people should get into trouble at the park and its beach — which unfortunately happened.

Youngsters liked to wade in the shallows off the park in the spring and fall, but there was a dangerous spot called “the black hole” that sometimes surprised people. While the surrounding areas were very shallow, this deep hole near the shore had been gouged out of the bottom by a shipwreck.

Since many people in those days couldn’t swim, “it seemed as though every once in a while, the black hole swallowed up another victim,” Lindquist said. Some who fell in drowned, but others were rushed to the Greenhoot house by rescuers and saved.

About 140 years after its construction, that house built for the Greenhoots at 404 Lake Shore Drive still stands and was documented as being “generally intact” in a 2023 report compiled by the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) in partnership with the City of Escanaba. The report, which inventoried 180 buildings in the 64-acre Ogden Triangle area, noted that the home had replacement siding but historic windows and a wraparound porch with columns and dentiled pediments.

Solomon passed away in 1925, Belle in 1928.

Lindquist’s presentation at the Bay College Heirman Center in April was the final of the Delta County Historical Society’s 2025 winter outreach series.